- Home

- Mark Polanzak

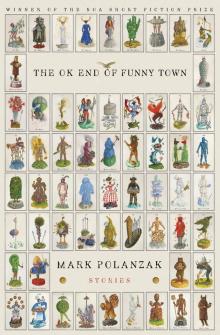

The OK End of Funny Town

The OK End of Funny Town Read online

THE OK END OF FUNNY TOWN

WINNER OF THE BOA SHORT FICTION PRIZE

THE OK END OF FUNNY TOWN

stories

Mark Polanzak

AMERICAN READER SERIES, NO. 34

BOA EDITIONS, LTD. ROCHESTER, NY 2020

Copyright © 2020 by Mark Polanzak

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reuse any material from this book, please contact The Permissions Company at www.permissionscompany.com or e-mail [email protected].

Publications by BOA Editions, Ltd.—a not-for-profit corporation under section 501 (c) (3) of the United States Internal Revenue Code—are made possible with funds from a variety of sources, including public funds from the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts; the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency; and the County of Monroe, NY. Private funding sources include the Max and Marian Farash Charitable Foundation; the Mary S. Mulligan Charitable Trust; the Rochester Area Community Foundation; the Ames-Amzalak Memorial Trust in memory of Henry Ames, Semon Amzalak, and Dan Amzalak; the LGBT Fund of Greater Rochester; and contributions from many individuals nationwide. See Colophon for special individual acknowledgments.

Cover Design: Sandy Knight

Interior Design and Composition: Richard Foerster

BOA Logo: Mirko

BOA Editions books are available electronically through BookShare, an online distributor offering Large-Print, Braille, Multimedia Audio Book, and Dyslexic formats, as well as through e-readers that feature text to speech capabilities.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Polanzak, Mark, 1981– author.

Title: The OK end of funny town : stories / Mark Polanzak.

Description: First edition. | Rochester, NY : BOA Editions, 2020. | Series: American reader series ; no. 34 | Summary: “Fantastical award-winning short stories that use humor, curiosity, and new twists on familiar situations to explore the boundaries of human connection”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019046009 | ISBN 9781950774050 (paperback) | ISBN 9781950774067 (epub)

Classification: LCC PS3616.O5575 A6 2020 | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019046009

BOA Editions, Ltd.

250 North Goodman Street, Suite 306

Rochester, NY 14607

www.boaeditions.org

A. Poulin, Jr., Founder (1938–1996)

For Alle

CONTENTS

1.

MEET FABULOUS STRANGERS!

Giant

Complicated and Annoying Little Robot

Genie

The Mime

Unidentified Living Object

2.

TRAVEL TO FANTASTIC PLACES!

The OK End of Funny Town

Our New Community School

Camp Redo

A Proper Hunger

3.

WITNESS MAGICAL THINGS!

Porcelain God

Gracie

An Exact Thing

Test

How You Wish

4.

EXPERIENCE SURREAL TIMES!

Out of Order

Ready Set

Oral

Kind Eyes

Used Goods

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Colophon

1.

MEET FABULOUS STRANGERS!

GIANT

The surprisingly few eyewitness reports stated that the giant walked, more or less, up Main Street from the west, stepping on the pavement and sometimes in patches of trees in parks and backyards, just before dawn. He stopped in the square, choosing to sit in the brick courtyard of the city hall, and leaned back against the big stone church, blocking off traffic on Elm and Putnam. Authorities discovered that he had successfully avoided stomping on parked cars and most of the city’s infrastructure, but that many swing sets, water fountains, jungle gyms, basketball hoops, grills, and gardens had been “smooshed.” No one knew if any birds or squirrels, likely sleeping in the parks and backyards, had been flattened.

The giant was still sitting in the square in the morning. A crisp and blue Monday morning in September. We found police cruisers and fire trucks parked with lights flashing in a two-block radius of the giant. Residents of the buildings within the zone were evacuated. Businesses were cleared and shuttered. There wasn’t a TV or radio station broadcasting anything but news of the giant. Live footage from a helicopter aired endlessly. The giant was taller than the city hall, the stone church, and the apartment buildings, even while sitting. Few of us saw him erect. He wore baggy tattered brown pants drawn by a red rope, an ill-fitting faded green shirt, and no shoes. He was human. He had human feet. Human hands. A brown satchel was strapped around his torso. He occasionally reached into the satchel to remove handfuls of giant berries and something else that crunched and echoed throughout town. He had long, stringy blond hair that fell on either side of his face, down to his shoulders—except in back, where a few strands had been pulled and tied up with a giant red band. No one had heard him speak. No one, as far as we knew, had attempted to communicate.

Since the giant seemed to have purposefully avoided crushing our homes and cars and had made no indication that he wanted to hurt us, we did not panic. Even the flashing lights and sirens did not inspire anxiety. The newscasts were not fear-driven. The reporters were curious. It wasn’t an emergency to anyone. It was awestriking. Eventually, the sirens were silenced. The flashers were shut off. You could hear laughter in the streets. When he reached for more food, there were gasps of joy. Children were held on shoulders to have a look.

The mayor, around three o’clock that first day, was raised up on a cherry picker and handed a megaphone. He said to the giant, “Hello.” The whole town was silent, awaiting a response. When, after a minute had passed and the giant had reached for another handful of food, the mayor repeated himself, adding his name, title, the name of our city, and a welcome message. To our great delight, the giant finally acknowledged the mayor, turning to him and emanating a ground-shaking three-syllable reply. But we could not understand. He was not an English speaker.

Professors from the language department of the university listened to the recording, determining that it was not something they had ever heard before. Linguistic anthropologists then went to work on the recording. They were not sure either. Verbal communication was placed on hold.

None of us went to work that first day. No child went to school. Many of us chuckled after remarking that the giant had put things in perspective. Our work seemed small. Our schools seemed small. The giant was all we cared about, and no one disputed it. How could we get our paperwork done with the giant down the street? How could any teacher concentrate on her lesson? There was no way our kids would do math problems with a real, live giant outside.

The influx of reporters and visitors slammed our streets and hotels and bars and restaurants that first night. You could talk with the person seated next to you. There wasn’t a chance they’d be discussing anything else. You could talk with anyone on the street. What do you do in a situation like this? He doesn’t want to hurt us. He can’t talk with us. He just looks tired, don’t you think? He keeps sighing and eating. Have you seen that he fell asleep? He sleeps with his head resting on the post office. Did you hear him snore? It sounded like low rolling thunder. Yes, it was soothing. And how he scoops gallons of water from the river with his hand?

Although the mayor had spoken with him, no one had attempted to touch him until the third day. After town m

eetings to devise the best plan to approach the giant, it was decided that the mayor and thirty policemen would carry flags with every conceivable peaceful symbol drawn on them. A peace sign. A pure white flag. Two hands shaking. The word LOVE. The word WELCOME. Pictures of people waving and smiling. Big flags. Big signs. They would walk cautiously up to the giant. We decided to make an offering. A barrel of orange juice. A loaf of bread the size of a school bus. We would place these before him and back away, waiting for him to notice that we were being kind. Then the mayor and policemen would walk closer and closer, extending hands and shaking each others’ hands to demonstrate what we meant.

Everything went as planned. But the giant never reached down to touch anyone. When the mayor got close enough, he touched the giant’s heel. The giant did not notice. This was frustrating. He ate the bread in a single chomp. He tossed the barrel of OJ into his mouth, crunched, and swallowed. He went back to sighing, wiping his brow and resting.

The giant is not interested in us. He is not curious about us in the slightest. He eats, drinks, rests, sighs, and sleeps. He has made no attempt to look any of us, save for the mayor that first day, in the eye. He has not thanked us for the food. He has not apologized for trampling our parks and gardens and recreation areas. He has not offered any help of any kind.

Not long ago, we began to wonder why we were so curious. What, apart from his obvious size, made him any more interesting than any of us? Why were we constantly talking about him, for days and weeks on end? Why were we fascinated every time he reached for his satchel or scratched his forearm? We all still talked to each other, but the conversation turned. We had waited long enough. We wanted to know if anything was going to happen, or if we were just going to have to live with a giant in our square. A dumb oaf that caused people to move out of their homes, that caused the government to move the offices of city hall and the post office to other buildings. If he were of normal size, he would be completely uninteresting. He would be mentally deficient, mangy. We would pity him. He contributed nothing. He took. He stole. He trespassed. He destroyed. He frustrated and incensed. He was boring.

When we travel, when we mention where we live and people ask, Isn’t that the town with the giant? we sigh, Yes. When we return home, we ask if it is still there. And our neighbors give the sarcastic answer, Oh, he wouldn’t go anywhere, don’t you worry. When we walk to the bus stop, we glance up at him with as much amazement as we do down to our watches. We know what we’d see. We would see a giant, sitting there, eating and drinking. We’d see a tired monster, not interesting enough to even hurt us. We’d see him wipe his brow. Then we’d check the time.

COMPLICATED AND ANNOYING LITTLE ROBOT

Um. It feels silly to admit this, but that little robot I bought was obnoxious. It was supposed to be fun. It’s a toy. A really, really advanced (and expensive) toy. But “fun” isn’t exactly the word that comes to mind when I think about the events that followed the purchase of that little robot.

First of all, he was way too commonsensical. And I don’t mean knowledgeable. The very first day, I was in the kitchen struggling with a jar of mayonnaise when from somewhere near the back of my knees I hear, in that monotone, condescending voice: “Why do you not break the vacuum seal with a knife around the rim.” I spun around to look at him. He looked right up at me with unwavering confidence. Those little square red eyes. I wanted one with blue eyes, but they were out. No one wants little square red eyes. Why did they even make them like that?

“What?” I asked it.

“Did you not hear or did you not understand,” he said. He continued to stare up.

I had heard, and I did understand. I reached into the drawer for a knife and slipped it under the rim and cracked the seal. The jar opened easily.

After a moment, I heard: “You are welcome.”

Second, when he wasn’t following me around the house being condescending, he was off fixing things. He tightened the screws on the banister so that it wouldn’t wobble anymore; he swept the foyer and vacuumed the bedroom; he reorganized the pots and pans in the cupboard. It was like my place wasn’t good enough for him. I didn’t ask him for any of that, and I had to thank him when he was clearly doing it for himself.

His anal-retentiveness came to a head while I was watching television and eating a sandwich. All of a sudden I felt it tapping my kneecap. I bent over, chewing, to see the little robot holding out a napkin.

“What the hell?” I said. “I thought you were reading!”

“I am finished. Here.”

“What, you think I’ll make a mess?”

“Will you not?” he asked without pitching his voice.

I was sure I’d get crumbs all over the place. “That’s not the point!” I hollered and stormed out of the room. In the doorway I turned around, sandwich in hand, to look at the little robot. He was still holding out the napkin but facing me. “You know who you remind me of?”

Then came the coup de grâce. That little robot lowered his little metal arm, dropped the napkin on the floor, and told me: “Make a mess. I do not care,” while zipping past me so fast I had to press myself against the jamb to avoid getting tripped.

This was followed by the little robot’s little martyrdom. He didn’t help out. He didn’t offer advice. He didn’t sweep or take out the garbage. He just knitted quietly all day long. When I asked him to help put groceries away, there was always a little pause before he placed down his needles and stitch holders. He helped, but he was mostly silent. Sometimes amid the shuffling of the paper bags I’d hear, “Do you want me to put the burger meat in the actual meat bin or do you want me to just throw it anywhere?”

“Throw it anywhere,” I’d tell him.

And I got it. I knew I had made him feel unappreciated. Trust me, his charade wasn’t subtle. So I did try, in my way, to make amends. It’s not like I wanted him to suffer. I just wanted him to chill out.

One night I knocked on his door, expecting to find him deep into a mock-cable stitch, and I didn’t hear a response. I knocked again and heard some scrambling, then “Come in.”

I entered cautiously and looked around the room. He stood in front of a towering corner of patterns, his metal hands behind his back.

“Looks like you’ve really done some work—” The rhythm of the sentence called for saying his name, but I hadn’t given him one. I saw his little metal arm quickly jab at one of his little square red eyes. And I swear I heard him sniffle. “You crying?” I asked him, incredibly curious. Could this wired metal contraption weep, or was he mimicking?

“What is it that you want?”

“I was wondering if you wanted to play some Monopoly with me tonight. We haven’t hung out in a while. So—”

He jabbed at his eye again. “That would be fun,” he told me. Or he asked it. I couldn’t really tell.

“Yeah. Fun,” I said.

He told me that he just needed a minute to finish up before joining me. I backed out of his space, careful not to break the treaty.

The little robot got Boardwalk and Park Place, but it wasn’t enough for my orange and red monopolies. The game was just the setting, though. I had become a little concerned about him. Although he was supposed to be different, and basically everything he did annoyed me, I couldn’t help but think that he would become fun if I gave him something he needed. I just didn’t know what it was.

So, I asked him: “You clearly haven’t been yourself lately.”

“Is that a question?” he stated.

“Yes. What’s wrong?”

“Oh, nothing.”

“Bullshit.” I drove my pointer finger into the tabletop.

“I am here for you.”

“Look: I want to be happy. You want to be happy. We can’t be happy unless both of us are happy. So what’s wrong?”

The robot passed his thimble token absentmindedly back and forth between his little metal hands. “I feel like,” he began, but stopped. “Nothing.”

“No, tell m

e, please.” I leaned forward.

“Okay. I feel as though you do not want me here. I feel as though I am incapable of doing what you want.”

“What?” I exclaimed while scanning the room. “You are the best, man.”

He looked up at me when I called him man.

“Robot,” I corrected with a forgive-me gesture. “Seriously. You are great.” I knew I was lying when I said this. I knew I wanted to return him. When he was condescending, it was bad. When he was anal, it was worse. Now, having this soul-sucking, moping, needy little robot around was the worst. I just didn’t want him to feel bad about it, you know? It wasn’t his fault. I hardly read the product description. I didn’t do any research. Hell, I jumped in the day after hearing about him. It was me.

“Really,” he asked. I think he asked.

“Oh, yeah,” I told him.

The following day I was on the phone with the manufacturer, asking about refunds, when it finally occurred to me to ask what they did with the returned little robots.

“What do you mean, ‘What do we do’?”

“I mean exactly that,” I told the guy on the phone.

“We crush ’em.”

“Like they do with cars?”

“Kind of. I mean, the robots are smaller. You know. You have one.”

“Right,” I said. “And you can’t just set them free?”

“What?”

“You, I mean I—I can’t just, you know, let him out the door?”

The guy on the phone told me I didn’t want to do that.

But I did do that.

I went to the ATM and withdrew five hundred bucks, got a child’s sized backpack, filled it up with yarn and some D. H. Lawrence books, and knocked on the little robot’s bedroom door.

He said, “Come on in.”

He was knitting and goddamn if I didn’t see a smile on the LED of his little damn mouth.

“This isn’t working.”

“How can I fix it?” he asked.

The OK End of Funny Town

The OK End of Funny Town