- Home

- Mark Polanzak

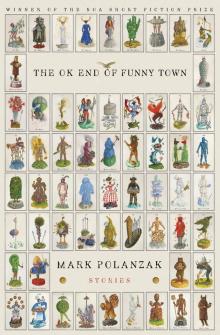

The OK End of Funny Town Page 3

The OK End of Funny Town Read online

Page 3

We told our sons and brothers not to believe these rumors. We warned them that to lie is wrong. We told our boys to stop talking with those other boys, because it could not have been our boys that invented these wild and harmful stories. Our boys did not believe in such illusions, such rumors, and they could surely tell when something didn’t actually happen in the world. These things were preposterous. None of this happened, and they had to know this. Nothing was true. None of this was real.

Tommy’s Dream

Tommy Morrow was four years out of high school. He had curly blond hair and a long, narrow, red face. He wore overalls. He worked for the town’s parks commission, and he drank with the other men in town at the Rare Duck Tavern every night. He was sweet and jovial. He laughed at our stories. He did not care that he was slightly out of place among the older crowd. He didn’t mind not always understanding what it was that our older men reminisced about. He was one of us. He had seen a poster, and had, of course, stolen it away. But since laying eyes on that poster, he had become increasingly quiet. Something had changed in him. He would not laugh with us. He now stared straight ahead, drinking dark beer, looking jumpy. We asked Tommy, finally, what the matter was. And he told us his dream of the mime.

It wasn’t a dream about the mime exactly, he explained, but because of the mime. It certainly had something to do with his upcoming show. Tommy was sure that the mime should not perform. Tommy had dreamed that he was blind. He fell asleep, and when the dream began, he could not see a thing. Blackness. Nothing but endless blackness in his dream. In his dream, he struggled to see, stumbled about, knocking into fire hydrants and telephone poles, calling out to anyone who would be around. No one answered. He could see nothing in this dream. He could only feel, touch—a mailbox, the grass beneath his toes, the rain on his face, the wind picking up his curly hair, the moment of nearly-imperceptible temperature change when a cloud moved over the sun. He could feel his own blinking eyelids. But everything was darkness in his dream. No change in color. He sensed every object, each element in his environment. But no, nothing was there.

We believed Tommy but told him that it was nothing to worry about. Nothing at all. He was fine. He could see perfectly well now, in the waking world. We tried to forget the dream. We eyed each other. We dispassionately and hurriedly drank more beer. Dreams aren’t real. They’re nothing in fact.

Reprints

The editor of our town newspaper reprinted reviews of the mime’s shows from Salzburg and Brussels. One school of thought had already surfaced, had already begun to dominate conversations at breakfast counters, post office lines, market aisles, and chess tables in the park—mimes are antiquated. A mime could not possibly entertain us. The newspaper articles, reviews, reprints—the entire section dedicated to the mime in the Wednesday edition convinced us all to the contrary.

A decades-old review of the mime’s show began with the critic, seated behind a woman in a red evening gown, her hair tangled up in several silver barrettes. Halfway through the mime’s show, this woman sneezed, then choked, then coughed. She was in the throes of a small fit. She stood to leave. While she stepped sideways down her row, with her back turned to the stage, the mime spotted her and described a yellow water balloon. The mime heaved it toward her. Without the ability to see the mime in action, the woman stopped short, turned around, opened her mouth in a silent scream, wiped off her face, turned again, and marched up the aisle, shaking water from her hands and onto the reviewer’s notebook.

The length of the mime’s shows varied considerably. Some were expectedly around two hours. Others were cut down to only fifteen minutes, either because of the mime’s irritation with the crowd, or frustration with his own performance. Some shows were sixteen hours, describing a day from the moment of waking in the morning light, to falling asleep at the end of the day, to closing one’s eyes, to dreaming.

City Folk

All of a sudden, our diners and markets and parks were a little more crowded. Our taverns filled up with men in suits. The porches of our inns and lodges became inhabited by women who wore long dark dresses and sat cross-legged in Adirondack chairs in half shadow. They were from the city, and they had come for the mime. They reminded us that things were changing. Big things were happening all around us. They reminded us that Tommy had withdrawn and seemed terrified most of the time, drinking with a paranoid arm around his bottle of beer. They reminded us that we all slept in homes where posters were kept in secret hiding places. The city folk reminded us that our women went missing at night, performing silent, dark, mysterious, and invisible descriptions. We had a show to attend on the weekend. How had the city folk heard about it? we wondered. But we made acquaintance with them—at the tavern, at the breakfast counter. We introduced ourselves, and they were receptive. Eventually, we all got to talking about the reasons for their visit to our small town: the mime. Some of the city folk claimed to have seen him perform, and that they would not miss another performance for the world. They said that they remembered the times when he played on the big stages of their city. They told us that they would not miss this, even if the performance were on the other side of the ocean. Some of them reported that the mime had not, actually, performed in their memory. The city folk told us that they, really, had not seen his act but had heard from friends or relatives or perhaps ancestors that the show was something not to be missed. They waited, with anticipation and anxiety, the same as we did, for the mime’s arrival. Some of them said the shows they had seen were miraculous, but when we asked for details they were cryptic. When we eagerly pressed for insight, they told us, “The mime is an artist, and it is difficult to explain.” Or, they claimed, “The mime has a way of showing you the wonder and strangeness in your own life.” Apparently, the mime had a way of showing you how to live, how to believe, how to breathe. When the city folk were drunk they shouted that the mime was a treat, that he had arrived in their city, their grand city, and that it would not be new to them, but they were eager to see our reactions—how they wished they could go back and see it for the first time, as we small-town folk were all about to do. But we could tell that they were anxious as well. They skated off at night and muttered to each other. They couldn’t sleep, awoke early, and shot looks at everyone in town as the day of the performance drew near. Where was the mime? What did he look like? The city folk knew the answers, they claimed. But they grew eager along with us. He must be in town already, they said. Where would he stay? The inn? It was booked with the city folk. Maybe he was in disguise. Maybe he was one of the city folk. But no—he would be spotted, a man like that. A true artist would not be able to blend in with the rest of us. But perhaps he could pantomime anything; maybe he could pretend to be just about anyone. The city folk drank our drinks to escape their growing terror, ate our food quickly and unmannered, shopped at our stores while spinning around, alarmed, at the tiniest of noises, read our newspaper in our park, with one eye on us. They were always aware of why they had journeyed here. They were here to see the mime. But no—nothing was that big a draw. Don’t bother. It’s nothing. It was nothing new to them, of course. Just a show. They shrugged. Nothing at all really.

Ticket Sale

The line stretched from the entrance all the way down to the iron gates of the park at the edge of town. A line of people rolling up hills and down into ditches. At the West End Theater, we waited for the booth to open. And when most of us were turned away—residents and city folk alike—there was a large skirmish and much yelling. The theater announced that something would be done to accommodate us. This was mysterious, but the ticket vendors seemed earnest. What could be done?

Those of us with tickets and those of us without tickets separated. The haves hopped on bicycles, jumped on the backs of motorcycles, placed lean legs in long dark cars, and vanished home to place the tickets in their secret hiding places with their posters. The have-nots wandered the streets aimlessly. We heard the words, “SOLD OUT!” We looked at the sign in the ticket booth, rest

ing between the shade and the booth’s window: SOLD OUT! We inspected the sign, reached in through the cut circular hole in the glass to touch the sign. We felt it, shook our heads, and stumbled down the block, then turned on our heels and marched back to the booth, inspected the sign again, and then, after making clicking noises with our tongues, stumbled away in any direction, being struck by motorists, bumping into others without tickets, getting pelted by errant soccer balls. We stumbled through the park, sitting on park benches, blankly regarding tree trunks, pigeons; we leaned against fountains for stability, turned in circles, stared at the great blue sky, and we fell on the grass. Our heads spun. We had no direction now. We strolled the streets at night, under the town’s streetlamps, pausing to examine and greet our own shadows, cocking heads, and wondering what those shadows would now do with themselves. We stepped into the tavern and were greeted with silence from the haves. We ordered drinks, drank them absentmindedly while staring at our shiny black shoes or the ceiling fans, spinning slowly around and around, and we left, forgetting to pay. We lost our direction. We were jostled again and again from our sleepwalking. Our dreamwalking, as it felt. People shouted at us. “Watch it! Pull it together! Get out of here!” We continued to stumble through the streets, through shops and diners, through the park, in the light of day, in the light of the moon. We did not show up to work. We forgot to eat at our dinner tables. We were no longer of use, it seemed. We were embarrassed and confused. Until. Until! Until the theater announced its solution. After that, we were, we have-nots, going nowhere, doing nothing. After the announcement, no one remembered that we used to wander. Nothing was wrong. Nothing had happened to us—we who slipped from starlight into the dark forests at the edges of our town.

Change of Venue

The theater made a deal with the shops and restaurants. All the businesses would see some of the money from the ticket sale, and the show would be moved from the West End Theater to Main Street. Those of us who had already purchased their seats would have first choice in the new seating arrangement, out in the street. The rest of us would presumably find seats toward the end of Main Street. We didn’t mind. We were delighted to have a chance to attend. Now, everyone in town, all the residents and the city folk alike were permitted to be at the mime’s show. We returned to work. We ate great big fat gleaming hams at our dinner tables, spent great deals of money at the diners and breakfast counters, slurping coffee and dabbing at the newly upturned corners of our mouths. We returned with good cheer to the tavern, raising glasses, buying rounds. We were back! We were a part of the town again. We had self-esteem and use. We were born again. And everything proceeded as if none of the midnight wanderings, none of the frequent disappearances ever happened. Nothing had happened. We were fine. Now.

Dissent

Some of us were never going to attend. Those of us with heart conditions or prone to stroke or aneurysm were not permitted to purchase tickets. It was for their protection. These were mostly the elderly, who were disappointed, and some did give protest, claiming that since they had been to war they could surely see a mime’s show. But no. They were not allowed. For their own sakes. But some of us declared disinterest from the very beginning. These were our raging, brooding, dark, disillusioned adolescents. They would not be duped, as they put it. Our disenchanted young people had no use for the mime. We handed them tickets in our homes, and our teens, our dark-haired girls, and cloaked boys would not take the tickets. They claimed to be above it. It was a gimmick, a big trick that conned the rest of us into believing something, and they would not dare believe. They were too smart. Too smart to be fooled, and they would not attend. We left them tickets on their desks, on their closed computers; we tacked tickets to their locked bedroom doors. If that was their decision, that was their decision. But we wanted to offer them the chance. If they changed their minds, we told them, here is your ticket.

But with their youthful conviction, with quite admirable gusto, they organized a protest in front of the theater. Holding up picket signs, they danced in a circle and chanted: “WHO WILL BE FOOLED? NOT US! WHO WILL BE SORRY? NOT US! WHO WILL BE FOOLED? NOT US!” We admired them. We watched them sing and dance with their dark eyes, their hoods, their youth. They truly believed themselves. And we liked that. That they believed they were right and we were wrong. Still, they had their tickets if they wanted to come. Nothing was going to harm them, we assured. Nothing was going to happen. It was fine.

The Show

It was marvelous. Turning of evening. Twilight is what it was. The sun was setting straight down at the west end of Main Street, behind the big black stage that stood ten feet high. The glass doors and display windows of the shops and restaurants along the street, with crooked “CLOSED” signs—all of them closed—reflected the orange, red, setting sun. And as the sun lowered, it melted and poured down Main Street, lighting our feet in a beautiful orange and dark red lava stream for a moment before vanishing altogether. The streetlamps lit up, clicked on bright, in domino succession—one, two, a thousand glowing yellow bulbs on down to the horizon. Tall men in crimson uniforms lighted torches at the end of every row of chairs set out on the pavement. We heard rushes of whispers, the squeaking of chairs. Mothers and sisters wore elegant evening gowns of black satin, of silver silk. Our women were walking, sitting, stirring crescent moons on our street. We were men in tails. In white suits with sapphire vests. Platinum rings shone in the torchlight. We watched as boys fiddled with their little bow ties, and girls shimmied in their best dresses and fussed with their French braids. The night was unusually warm. The torches burned us, as we sought our seats down the aisles. Our entire citizenry was here, stretching down Main Street, side by side with the city folk, wearing pearl necklaces, gold pocket watches. Everyone had a queer smile tucked behind flattened lips.

We all felt like one powerful being—our town come alive! We were people gathering in the heart of our fair town in our best dresses and suits, after preparing in our homes for hours to appear sleek and elegant, comfortable but formal. Louise placed her pale hand in the palm of a man, who kissed her fingers. She crossed her legs beneath her emerald dress. Tommy, with a friend’s arm securely wrapped around his shoulders, took deep breaths in his tuxedo and smiled nervously. We spoke to each other in soft voices, voices of respect, and used words as we never had before—as if these were the last words we would ever speak to each other, or maybe the first. If a lady bumped us, searching for her seat, we gestured in slow chivalry. The moon and stars revealed themselves. Of course, they were up in the sky all along, during the daylight, but we could not see them, and we felt that those sparkling white dots in the sky belonged just to our town, for our one evening out on Main Street. The moon hung low, tempting us to touch. Warm autumn evening. This was our place, and we liked it very much. Torches flickering. Crackling. Moonlight. Men, women, children in long rows. Our faces under dancing firelight.

Some of us had work to do at the show. Some of us were standing behind great spotlights on raised platforms positioned periodically above our heads throughout Main Street. Some of us were waiting in the wings of the great black stage, ready to yank the golden tassels, to pull back the curtain. They held on tight, waited for their cue. The men behind the spotlights watched the men in the wings. The men in the wings eyed the men at the spotlights. We, the audience, settled into our seats. We heard whispers. We heard children shifting in their chairs, restless. Then we heard the final squeak of the last person finding her seat. Finished. We took a long deep breath together and gazed up to the long, high, black stage on Main Street and awaited our finest guest.

And we waited for several minutes. Long enough for some of us to risk a cough in the silence. Some of us reached into our purses, fetching handheld mirrors, quickly adjusting our cameos and hair with sharp, anxious faces and pursed lips. Some of us smiled to our wives and then turned our gazes again to the stage. Some of us patted our children on the thigh and calmed them. Some of us pulled out long gold chains attached to

glinting gold pocket watches and glanced with one eye down at the hands. Some of us looked to the men with spotlights, who stared at the men in the wings. We stared at the men in the wings, who stared at the men with the spotlights. Then we sat up straight once more and waited.

Then some of us whispered. Some of us doubted. Some of us wanted to know what was wrong. What was the matter? When was it to begin? Were we mistaken? We couldn’t be mistaken—we were all here, every inhabitant of the city, even the cloaked and brooding adolescents had grabbed tickets from their locked doors and arrived late, bringing with them the insistent elderly with their canes and wheelchairs, hiding in the alcoves of storefronts. They were sheepish, but we smiled to them. Everyone was here. A town as a whole could not make such a mistake: The performance was tonight. Positively.

The torches whipped in the rise of a chill wind. We held our lapel flowers and ribbons in our hair. We leaned into our husbands. We put arms around our children as a great gust of wind knocked off hats and extinguished some firelight. Then the wind ceased, and we again stared at the stage. We stared. We leaned forward. We squinted. We blinked. We checked watches. We sat and waited. We cocked our heads. A long, dark, blank stage. The torches. Our town. The high black empty stage. And we waited. Somewhere someone let out a clear and loud “Ha!” And then we stood and applauded. We clapped and whistled through our teeth. We held our children up over our heads so that they could see—so they could have a look and remember this moment. We laughed and hugged. We cried. We shouted. We grew hoarse. We climbed up onto our seats and applauded—the entire town and its newcomers—until the sun rose up behind us, over Main Street, and, with its glorious light, showed us all where we were and how we could perform.

The OK End of Funny Town

The OK End of Funny Town